Why do we say “amen” at the end of a prayer? Or, better, why do we usually not say “amen” at the end of a public prayer? What does this word even mean? I’ve thought a lot about these questions the past several months and it has led me to certain convictions for why I say “amen” and how public prayer works.

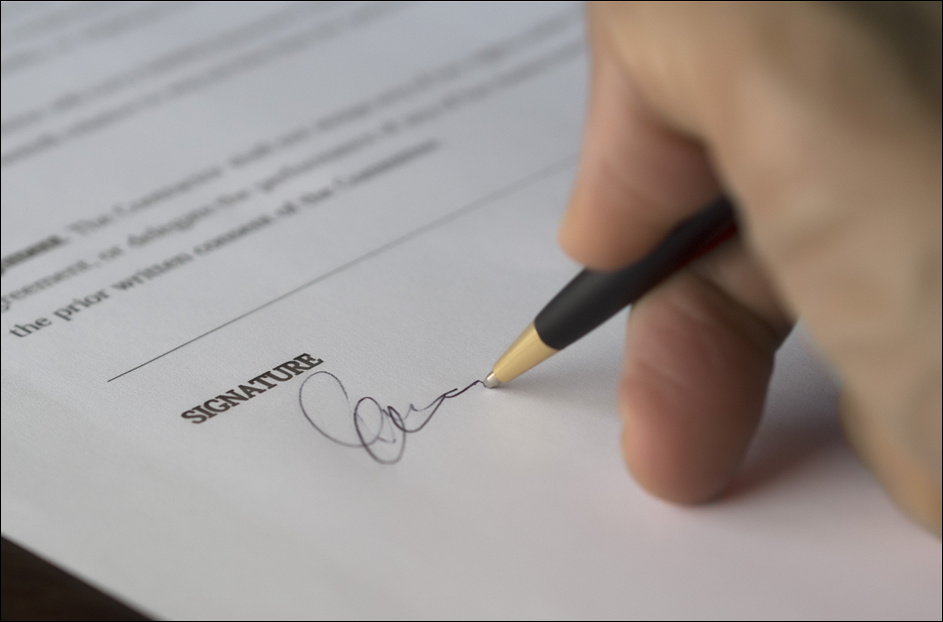

The English word “amen” comes from the Latin amen which comes from the Greek amēn (ἀμήν) which comes from the Hebrew amen (אָמֵן). The Hebrew word was used as a declaration meaning “surely!” or “let it be so!” or “it is trustworthy!” It was spoken by the Israelites after Moses pronounced the curses on those who broke God’s commandments in Deut. 27. Here, to say “amen” is like signing your name on a document written up by another person. It shows that you agree with the terms of what was said and acknowledge them as your own. This is why doxologies (i.e., praises of God; e.g., Jude 25) always end in “amen.” Additionally, whenever someone spoke in a Christian assembly, the listeners would say “amen” in agreement with what was said (see 1 Cor 14:6).

I used to think that when I listen to a prayer lead by another, that I was supposed to say my own prayer in my head and follow along with the contents of what the person was praying. However, as my understanding of what “amen” changed, so did my prayer life. For in our public prayers, we ought to say “amen” when we agree with what was prayed. By saying “amen,” we metaphorically sign our name to the prayer as though we ourselves said it. Thus, we all – men, women, and children – ought to say “amen” at the end of a public prayer, given that we agree with what was prayed. We also should not be afraid to say “amen” during a sermon when we agree with the lesson. This is what the early church did. We should practice it all the same.